The end of this month marks five years since I set out on the odyssey that’s become The Harebrained Press Project. To mark this milestone, I’ve decided to write a reflection that will include some of my more personal experiences—challenges and observations I haven’t mentioned in previous blogs—along with photos not shown before. This retrospective will be in a number of parts.

Aside from sharing with you something that has changed me and shaped my life, I hope that these accounts might encourage others engaged in a creative practice to value it in all its phases. When I say ‘creative practice’ I mean this in the broadest possible sense: not just artistic projects, like mine, but fulfilling life goals—even if your goal is to live a fulfilling life. I’ve learnt that, contrary to what we’re often told about extended projects (and about life, for that matter), challenges and obstacles can be good for us and our progress—and for the progress of our work. Resistance, for me, has been a force to push against, a powerful motivation that has ultimately helped me to become resilient, resourceful—and to get to where I need to be. The one condition, I’ve found, is that I remember it’s all a big adventure.

Part One is about the motivation behind my project and my initiation to the printing world—one of ‘utter dismay’. It’s also about how, three weeks into my project, I suddenly went ‘down the rabbit hole’.

Wouldn’t it be awesome to make my own book

myself, the way I really want it: printed in the old

way, bound by hand, with marbled endpapers

and all that…

Such was my innocent zeal, back in 2016, which propelled me towards a venture that was virtually impossible. But, of course, I didn’t know that at the time. One of my favourite sayings comes from another writer and print-maker, the visionary William Blake. ‘If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise.’

I knew all about ‘persisting in folly’. I’d spent ten years writing and refining my short stories only to have them come back time and again from mainstream Australian publishers with the same comment: ‘beautiful writing…but it doesn’t quite fit’. What they meant was that my stories either didn’t align with the preoccupations that were fashionable at the time or that they didn’t slot neatly into the parameters of genre. I’d watched other unconventional writers (and very good ones) languish before the ‘tyranny of trend and genre’. Some had succumbed, changing their work to suit the market; some had sought to reach readers through self-publishing. Others had quit. In 2016, having had a break from writing for a year in despair, I was on the verge of the last outcome. Unwilling to compromise the vision that had brought these stories to life, I’d come to a crossroad. But a nagging question stayed with me: what do I really want? In the end I realised it was pretty simple. I wanted to turn this ‘beautiful writing’ into a beautiful book.

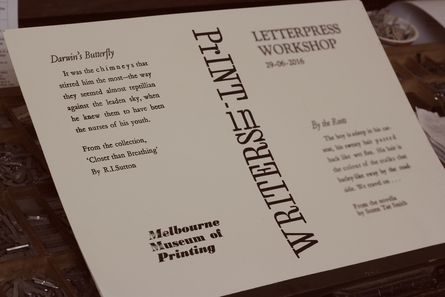

For months I turned second-hand book shops upside down looking for ancient trade manuals; and I enrolled in a letterpress printing workshop at the Melbourne Museum of Printing (MMoP). The museum’s course appealed to me for its emphasis on traditional skills over the methods used by most letterpress printers today. Contemporary studios print from photopolymer plates which are produced from digital documents and imagery converted via a photo exposure method. I was more interested in what happened before the computer made typesetting easy. Individual letters, punctuation marks and spaces cast in metal (known collectively as ‘type’) were arranged (‘composed’) by hand and locked into a metal frame to become the ‘forme’: a relief model of the document in reverse, used to print from on a press.

The hand-composition method of traditional typesetting held a romantic appeal for me: the idea of actually ‘building’ the book, one character and space at a time.

I remember the moment I stood in the workshop at the museum and looked down at my first forme. I felt utter dismay. Here were thousands of pieces of type, arranged just so—and in reverse!—each relying on the next to hold its position in the whole. It was like the cruel, impossible task set for the miller’s daughter in Rumpelstiltskin. How could I possibly spin all this lead into gold? Aside from the mountain of work, it was a mathematical nightmare to someone who’d always struggled with numeracy. My high school rehabilitative Maths teacher, Mr. Lawson, came to mind. I remembered how his kind, earnest face and soft voice would harden as he reproved me for my interminable antics up the back with the boys. Here, before me, was my karma.

This feeling was compounded by the printing course itself. It was comprehensive. Michael, the museum’s director, possessed an encyclopedic knowledge and was eager to share it. He covered the history of printing from ancient China to the present day and included an explanation of every machine that had been used in the trade—examples of which he seemed to have on site. My friend and I were then invited to wander the cavernous museum warehouses to choose from a boggling array of type cases in designing, hand-setting and then printing our own poster. Twelve hours later, exhausted and relieved, we left the museum, cradling our stack of prints with the same reverence that Gutenberg must have his first bible.

The workshop gave me an authentic encounter with the trade, one that encapsulated my own later experience of printing: as a delightful ordeal. It left me overwhelmed by my own ignorance and the resistance I was yet to face. But face it I would. I’d told too many people what I was going to do. And I was hooked.

Three weeks after this introduction to printing, I got a startling phone call. Michael had been impressed by the enthusiasm my friend and I had brought to the workshop. Would we represent the Melbourne Museum of Printing on an all-expenses paid trip to South Korea? The International Association of Printing Museums was holding its inaugural meeting in the city where the oldest existing book printed using movable type was made, and MMoP was invited to speak at the convention. Daunted, but faithful to the harebrained spirit, we agreed.

I won’t detail the epic roller-coaster ride that was my Korean adventure (you can read about it in previous posts). Meeting the ‘who’s who’ of the letterpress printing and printing heritage worlds, including representatives from the Gutenberg Museum in Germany and the Smithsonian Institute in Washington was an intense buzz. Standing behind a podium and presenting a talk about the history of printing in Australia to these people, a full media cohort, and the sixty other delegates, was the single most terrifying experience of my life. Through the trip I learnt many things: that no force under heaven (or in it) can make me sleep on a plane, and the degree to which terror and rich Korean food don’t mix. But I also learnt about inner resources I never knew I had. Six days later, fatigued beyond coherence and several kilograms lighter, I returned home, went to bed and slept for two days.

I returned to the museum and, with Michael, started planning the technical aspects of printing my book. I was grateful to him for his mathematical prowess—and for his optimism. One of my misgivings was that someone in the field might tell me that what I wanted to do wasn’t possible. This fear came back to haunt me time and again in the years to follow as I agonised over seeking others to help me. I saw the project as my final chance to do something with my writing, a last-ditch effort before I buried my stories forever. I was terrified of hearing the nay word again.

But I needn’t have worried with Michael. For him, everything was possible—and he had even greater plans for the project. Not only was I to print my whole book at the museum, but I would also cast all my own type on one of its casting machines. The problem was that the machine had been out of action since the 90's and needed an electrician to set it right. Michael was eager for this to happen, and well-intended, but the museum stood on the threshold of financial ruin and couldn’t afford the outlay. After waiting months for this miracle tradie to show up, I decided I’d need to take matters into my own hands.

This was to be the prevailing theme of the project: row your own boat.

Write a comment

Shaun Clarke (Wednesday, 30 June 2021 05:30)

Congratulations Beck, thanks for sharing, you are an inspiration

Branka Juran (Wednesday, 30 June 2021 05:40)

You are an amazing and inspiring young woman.

I have thoroughly enjoyed this journey with you.

Kerryn Frances Anderson (Wednesday, 30 June 2021 06:10)

What an adventure Beck. So proud of you, can't wait for the grand finale cx

Marg MacGillivray (Wednesday, 30 June 2021 06:40)

Your determination to complete this project is both amazing and inspiring.

Keep at it, I know you have the tenacity to see it through. I look forward to holding your book and turning it’s pages.

Your Mumsy.

Steven Bright (Wednesday, 30 June 2021 17:31)

Well done Bec you have the drive and dedication to achieve your dream of publishing your own book.

I know some of the hurdles you have faced, you have gone over them, around them and through them.

I am looking forward to you getting to the finishing line. You are a champion of Letterpress.

Chris Atkins (Wednesday, 30 June 2021 20:06)

What a wonderful experience to share. Your tenacity and ability to take on complex tasks of many hues is inspiring. Great info on the earlier printing methods has been dispensed through your writings. Thanks for taking us along your journey.

Beck Sutton (Thursday, 01 July 2021 02:46)

Thanks everyone for your kind, encouraging words. Your interest in the project helps me to keep going. I'd love to thank you all personally at the launch. Watch this space!