Buoyed by the response to our first fine press edition, Closer than Breathing, Kain and I have been keen to use the skills and equipment we’ve gained in the book’s creation to craft a new line of Harebrained products. The question foremost in our minds since the launch back in March 2023 has been What will we create?

We decided that, whatever we made, we wanted it to be inspiring. It must be made from quality materials—and these crafted using the best methods. Being a writer who has always valued the act of writing with an actual pen on paper—and being someone who has always found that my writing materials help me to get in ‘the zone’—I was keen to try out a new binding style, one that would bring together all the qualities of my dream writing journal. My journal must appeal both to the smooth passage of the pen over the paper and to the senses; it would be sturdy and feel good in the hand.

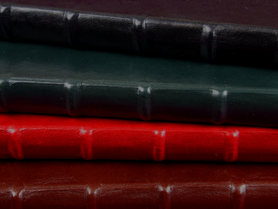

The flexible binding style appealed to me for my Harebrained journals because it features these qualities, and also because of its historical significance as the favoured binding structure between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries. Flexible binding is a method in which each page section is attached to the next by means of a thread sewn around perpendicular chords, lending the binding superior strength and flexibility. In the finished book the chords project as bands along the spine with the covering material applied directly to it—as opposed to later designs which integrated the cardboard tube that we see in a hollow-backed binding.

Flexible Binding

Hollow-Backed Binding

When the book is opened, the spine flattens, allowing for an easeful page spread. As a method, this binding style can be challenging to do—and is generally only used for books worthy of a fine binding—because the sewing is exacting and the raised bands require special tools, coverings and treatment to be well-finished.

Many binders forgo the method, choosing instead to emulate its aesthetic by sticking strips of cardboard or leather to the spine prior to covering; while these ‘false’ bands can be fairly convincing, they add nothing to the book’s structure.

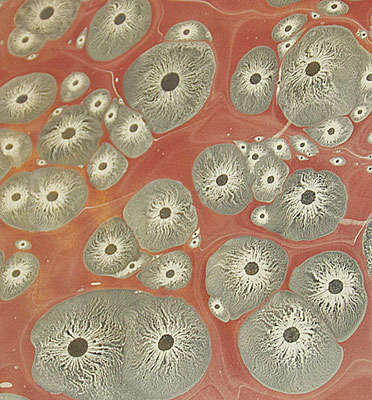

I find I work best when I throw myself in the deep end; so, after binding a couple of prototypes to finalise sizes and colours as well as the best method and materials, I set to work in the bindery with a timeline of two months. My goal was to have a good stack of journals ready for display and sale at this year’s Clunes Booktown Festival. As usual, I wanted to do everything in-house, and this began with the arty stuff: paper marbling. Over three days I treated, marbled, and then re-marbled my stock for the cover boards and endpapers. I was excited to try out two unexplored novelties: a beautiful big marbling bath that Kain had forged for me in his woodworking studio, and a new marbling pattern called sunspot. Sunspot—also known as ‘tiger eye’—is notoriously difficult to do well because the paint and chemical combination is worthy of a degree in chemistry. My first attempt didn’t turn out as I’d expected, but the results were so surprising and quirky that I decided to use them nevertheless.

I was also surprised to find that I enjoyed sewing the page sections as much as I did. There is something that I can only describe as soulful about crafting traditional bindings using natural materials, about turning waxed linen thread around hempen chords knowing that they will unite in something elegant and useful. Then, the chords are frayed out with a needle and comb until they resemble flaxen hair. These form the ‘slips’ used to attach the cover by lacing them through holes pierced in the boards. The design is as simple and ingenious as the fastenings on medieval attire, and just as charming.

Next, I trimmed the page edges using my book plough. The plough is a device that was invented in the 16th century for page-cutting. A wooden sled glides along runners fixed to the top of a book press. As the sled is pushed back and forth along the runners, a handle is turned and a blade advances into the paper. See the plough at work here.

Before the plough, binders had used a sawing blade to trim down their books—a difficult process with a messy finish. The plough makes the cut smooth, straight and polished. But, like everything done by hand, it takes time. Even so, my plough is one of my favourite pieces of kit in the studio. Though its origin lies as far back as the 1860s, it still works beautifully because it was fashioned in the true spirit of the traditional crafts—that is, to be of sound, good use. And, like the skills that were attained by the traditional craftsperson, it was meant to be passed on.

One of the most ticklish steps in creating my journals was attaching the leather to the ridged spine. Wielding a razor, a knife and a sanding block (carefully, and at different times!), I thinned the leather down at the cover joints and along the sections where it was to be turned over the edges of the boards. Then, I moistened the leather with water and paste and started coaxing it over the spine chords, being careful not to stretch or bruise it.

In traditional binding the ‘simple yet ingenious’ is employed once again to encourage the leather to conform to the spine—with the use of cotton tie-up string. The string is neatly crisscrossed around the chords in a configuration that requires a numbered diagram, a lot of hand contorting, some tangling, and a few curses. But when the books are tied up in their neat, firm lacings and you see how handsome they are starting to look, you forget what a handful they have been. And you realise you are on the home stretch now because from here the real tricky parts are done and it’s all about covering and finishing: gluing the marbled paper to the boards, sticking down the endpapers, waxing and polishing the covers.

My Harebrained artisan journals were finished in time for the Clunes Booktown Festival, and I was delighted to find as I laid them out on the table that they were in keeping both with our first fine press edition and with Kain’s striking card designs. Unfortunately, two of my journals had fallen by the way in those binding mishaps that occur in just about every new run. Late one night, delirious with weariness, I had cut a pair of attached cover boards too short; and I had ruined another journal in the final step of gluing its endpapers to the boards by warping the pages out of alignment with its covers. But when you are doing what you love and doing it by hand you learn to be philosophical about these losses. They usually only happen once because they rouse your greater care, awareness and the physical adroitness that you need to work your materials with harmony. Care, awareness, harmony in the work of our hands and minds: creating books has taught me that these are qualities that cannot be too hard-won.

At the Clunes festival it was lovely to see that the passion for books is still very much alive. We met artists, collectors, writers, readers and creatives who were keen to hear the Harebrained story and also to share their own, which invariably included a love for art, for creating, and for books. After spending many hours, days, and weeks in the Harebrained studio preparing to be there, this was inspiring and we've returned home with new ideas and a renewed enthusiasm for our practice.

Check out our Artisan Journal page here

See our Fine Press Gift Cards here

Write a comment