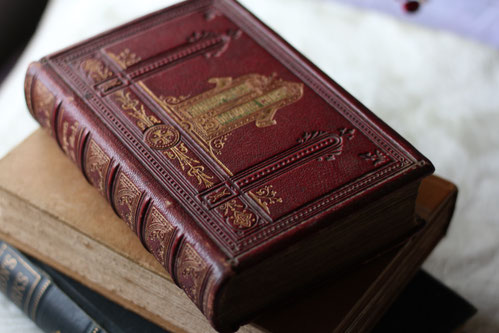

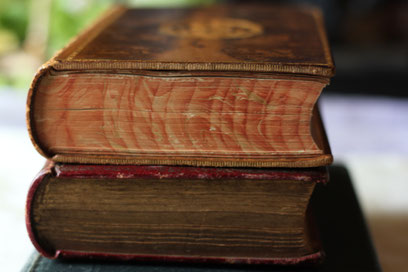

My earliest memories of reading are associated with the sensory qualities of books: the crisp smell of new books; the rich scent of the old; sharp paper corners, or thick, velvety card. In fact, I’m sure that it was these qualities that made books special to me as a reluctant, early reader and enticed me to overcome my difficulties—so that I might one day be able to draw down even the heaviest tome from the shelf and enter the mystery of those atom-thin, closely-printed pages. To me, a book has always seemed like two hands closed over a secret; and something of this secret is suggested in the printing and binding.

For the past sixteen years I’ve been working towards creating a book of my own. During this time I have come to see that there are many limitations in the mainstream publishing world; and I have come to know that this is not an option for my work. The positive side of this was my realisation that, if I were to self-publish, I might do whatever I like with my book—I could produce it in the way that is most appropriate to its own particular mystery.

When I made the decision to self-publish I didn’t have even a rudimentary understanding of printing. All I knew was that the common method is called ‘offset’. But I also had a vague memory of an earlier method—a method that had appealed to me when I first heard of it because, beyond its intended utility of reproducing text, it has incidental qualities: it leaves an impression in the paper; and, under close inspection, no two characters ever print exactly the same. It is tactile, idiosyncratic—and it was the means by which my favourite books and writers had been printed. I decided that this was the way I wanted my book to be printed too. I started to investigate…

R.I. Sutton.

Next Chapter: About Letterpress Printing

Write a comment